…With apologies to Paul Harvey.

One of the frustrating things about writing a book is that often you find stuff about the subject only after it goes to press, and too late to insert into the manuscript. A prime example is the following tale, which only surfaced after the writing was done.

Jesse Avritt Bryan was born in 1815 and raised in Clarksville, Montgomery County. His father served in Congress but died when Jesse was only a youngster. He later became a partner with his brothers in a mercantile firm, and was quite popular – if touchy. “he was of a proud and sensitive nature,” one friend later wrote, but one that “could not brook aught of insult.” This sensitive nature got him into serious trouble in the summer of 1838 when he was 22.

Somehow he ran afoul of the starchy Marius Hansbrough, a 37-year old fellow Clarksvillian. Hansbrough was married, and his first and only child – a daughter – had been born earlier that year. He’d also apparently had a few hard knocks to deal with – in 1832 while he was attending a celebration of Washington’s birthday at Shelbyville, Kentucky, a cannon had exploded and his right arm had to be amputated from the resulting damage. In 1836 he had partnered up with G.A. Davie and purchased the Washington Hotel on the public square, the most prominent hotel in Clarksville. It would end up being a house he never left.

Exactly what their beef was is unclear, but one account says that Hansbrough had – correctly or not – interpreted some action on Bryan’s part as an insult. So angry was he that Bryan was later informed that Hansbrough had gone hunting for him with a bowie knife until his friends intervened. However, rather than meet with Bryan to settle the issue, he chose to shun the youngster and snub him. For over a year the two tiptoed around the ticking time bomb between them.

Finally, on August 4, 1838, Jesse Bryan walked into the Washington Hotel and met Marius Hansbrough face to face. He greeted the older man in a friendly fashion, but Hansbrough coldly told him that he wouldn’t associate with someone who was out to assassinate his character. An argument ensued which ended with Hansbrough threatening to “wring his nose” and “cut off his ears” if Bryan ever angered him again.

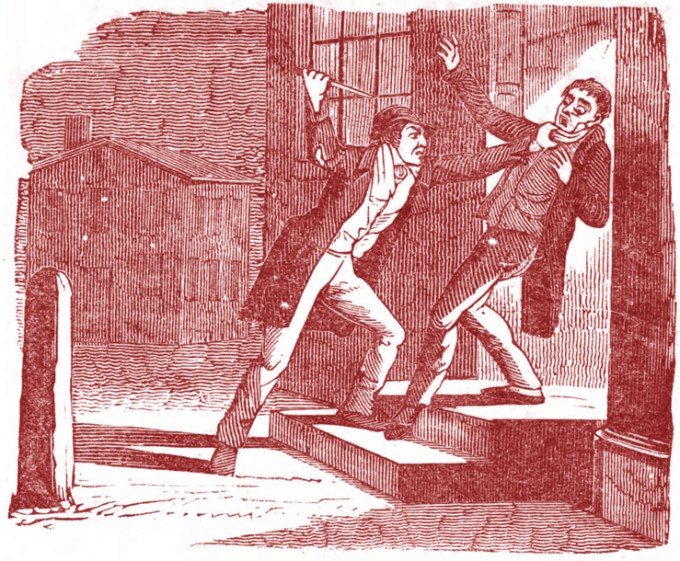

At that, Bryan stormed off and procured a bowie knife before heading out to find his adversary. On the sidewalk in front of Barksdale & Cromwell’s store they met and Bryan said he supposed Hansbrough was “prepared.” Almost immediately the fight began. Apparently Hansbrough raised his riding whip with his good left arm and tried to hit Bryan with it. Bryan slashed the upraised arm, but the cut did no damage as the sheath was still on the blade. He flung the sheath into the street and struck again, this time stabbing his target in the ribs on the left side.

Bryan fled while Hansbrough was carried back into his hotel and a doctor was summoned. Sadly, nothing could be done to stop the internal bleeding, and he lost ground rapidly. At 10:45 PM on Sunday, August 5th, Marius Hansbrough died.

Bryan was later apprehended and tried for the killing, but apparently he was acquitted on grounds of self-defense. However, this wasn’t the last scrape he would become involved in. His next fight would also involve a posh and popular hotel, this time on Nashville’s Public Square. And once more, it would be a duel to the death involving guns, knives, and a secret weapon. What happened?

You can find out in the pages of my book…